The other day I was reading through an old issue of Esquire Magazine (for the articles, I swear!), and I came upon something that made me realize how ahead of the curve the contemporary handmade movement really is. Unlikely perhaps, but read on.

In a typically cheeky-yet-informative piece titled the “5 Minute Guide to Oil,” the magazine asked some hard questions: “Can we get oil from someplace other than the Middle East?” (Basic answer: Yes, but it’ll run out around 2025) and “What is Peak Oil?” (The recognition that oil is a finite resource and once supply outweighs demand in about 20 years it’s gonna hurt.)

It also asked the question “Should we be scared?” (Essentially, yes.) By way of responding to this question, it offered a Saudi saying that, once I read it, set off a flashbulb in my brain. It may be scary in terms of oil, but its ramifications for craft are inspiring. The saying goes like this:

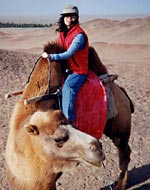

“My father rode a camel. I drive a car. My son rides in a jet. His son will ride a camel.”

Opting to ignore the chauvinism for a moment, “Exactly!” I exclaimed to myself, as I excitedly grabbed for the Aug/Sept issue of Bust Magazine at my side. I love this issue for the wardrobe-altering sewing instructions it offers. And I love how empowering the magazine is generally to anyone craving a little DIY self-sufficiency from the global economy.

My thought was that perhaps in some ways, Bust magazine and many other recent cultural phenomena—a resurgence of stitch-and-bitch gatherings, Church of Craft events, many DIY books and magazines, the blogs kept by potters and bookbinders, and so on—are sort of preparing us to ride the camel before we really have to. Today we can knit a warm scarf at our leisure while riding in a jet. This struck me as quite profound.

Among some of the people who make things by hand for a living there is an attitude of knowing a secret. This secret has to do with having access to a way of life most of the rest of us have abandoned for the (perceived) convenience and variety of the global marketplace. It has been only a few dozen years since we American consumers started sending our dollars overseas in exchange for the goods we use everyday. 100 years ago, our good were made much closer to home, even in the home. Imagine sewing and mending clothes for yourself and your family, or building your own house out of the trees on the land, not because you want to but because that’s what you have to do to survive.

Fossil fuels like oil and coal had a lot to do with changing all that as it became feasible to power factories and transport goods across great distances. Today, we usually don’t think twice about picking up some new dishes on sale at Crate & Barrel, or ordering a pretty throw blanket from Pottery Barn. But where are these items made? And who is making them? How are they getting here? And who is profiting from the money you paid for them? Is this better than the locally handmade option?

There are plenty of questions about labor fairness and corporate bottom lines to be considered here. But today I’m interested in the matter of energy, fuel. Oil. On what sort of power are factories in China and India run? What powers the shipping of items from these factories to us? What fuels the trucks from the ports to stores? How do we get to the stores? How do the stores keep their lights on? For the most part by far, the answer is oil.

There is an opposing argument that says it is actually more costly in terms of amount of oil per, say, head of garlic to drive a small truck down from upstate than it is to steam a cargo ship from China and then drive a tractor trailer truck with a bulk load across the country. And it may be argued that small-scale production is not as energy efficient as large-scale production. And surely there is a numbers game that may be played here.

But what will happen if we suddenly don’t have the oil needed to fuel our consumer economy? What will we do? We will go back to riding camels. That is to say, we will return to relying upon local producers to supply our needs: skilled local potters, shoemakers, furniture builders, toymakers.

There may come a day when taking a pottery class is less about finding a creative outlet and more about making a living producing tableware for the local market. Imagine a day when the artisans of the world are flush with plenty of locally-based work and the globalized corporations are shutting down because they can’t fuel their vast needs any longer. I'm not saying we should rush things. But it is a vision like what I think some craftspeople see on the horizon.

What do you see?

(Read a response to this post in Design Diary.)

1 comment:

A great and thoughtful post. It's something I certainly think about from time to time. I've actually posted an entry about this on my blog. Can't wait till your web site opens!

Post a Comment